How to write about side effects in plain English

We all know that medicines have benefits and risks. Doctors and patients weigh up the benefits of starting a medicine with the risks involved.

One aspect of the risk of a medicine is its side effects.

Medicines do have unwanted effects, and these need to be accurately disclosed to the patient.

But disclosing side effects in written patient information is “as much an art as a science” says Sylvia Roins, Chair of the Electronic Distribution Working Group for Consumer Medicine Information (CMI).

In Australia, the new CMI template helps medicine sponsors communicate side effects in a more user-friendlyand patient-oriented way.

Here, I’ll look at how to present side effects in the new template. Plus, I’ll give you some tips on how best to write about them using the new CMI template.

Side effects in the new CMI template

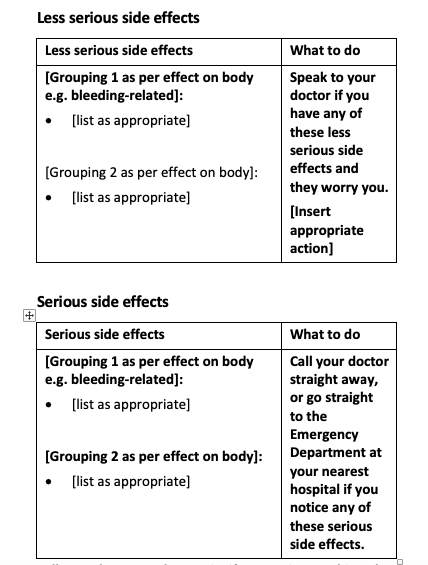

You will notice that the new CMI template uses tables instead of dot-point lists for recording side effects. Researchers found this design improvement helps readability and reduces complexity for the consumer.

The new one-page CMI summary needs to include just a few of the main (most common, most serious) side effects. Note the hyperlink to the tables in the full CMI, where you provide more complete information.

What to include

According to Schedule 12 and 13 of the Therapeutic Goods Regulations 1990, a CMI must be consistent with the approved Product Information (PI), and legibly written in the English language in a way that a consumer can easily understand.

The general language of the schedule leaves a fair bit of latitude for the sponsor to decide:

what side effects to include

how to write about them.

And this is where CMI writers can get a bit stuck.

Does this mean we transfer every known adverse event from the PI to the CMI?

In many cases, it would be unreasonable to insist that we duplicate the entire Adverse Events section of the PI in plain English in the CMI. This would rarely be in the best interest of the information user.

So, we need to strike a balance between:

informing patients of the extent of possible side effects

not overwhelming patients with an inordinately long list of side effects, potentially losing significant side effects in a sea of ‘less important’ ones

making sure patients know what to do if they experience a side effect.

“Writing a CMI is as much an art as it is a science”

Dr Roins, who is also an experienced CMI writer, acknowledges that the side effect section of the CMI “is usually the hardest to write”. She recommends the following as a good rule of thumb when considering what to include in the side effects section:

most common

most serious

most noticeable to the consumer

Once you’ve selected the side effects, you can group them:

into less serious and more serious

by how they relate to the body (e.g. gut-related, allergic reaction related).

You can judge the severity of a side effect by the action that a consumer needs to take if they experience it.

If they need to see a doctor immediately or attend the Emergency Department, that would be a more serious side effect. If the side effect is notable, worrisome even, that would be a less serious side effect.

Crucially, you must write each side effect in plain English and as it is most commonly perceived by the patient.

Equally, we need to avoid including asymptomatic side effects (such as high blood pressure) in the tables. If a consumer cannot perceive a side effect without a medical test, don’t include it in the table.

Instead, for side effects measured by medical tests or checks you can use a general statement (before or after the table) such as:

“Your doctor can only detect some side effects (such as x,y) with a medical test. Attend any medical appointments needed to monitor these side effects.”

What about the frequency of side effects?

There’s no doubt that some patients are interested in how common a side effect is. It can be useful information in helping a patient make an informed decision about their medicine.

However, writing about the risk of occurrence in an understandable and usable way is fraught.

In fact, studies suggest that trying to express side-effect frequency qualitatively (i.e. rare, common) led to overestimation of risk by most consumers.

Because of this, the CMI template does not group side effects by their estimated frequency.

The benefits of user testing

In writing for consumers, we need to chart a path between precision and usability. This is why it is helpful to user test CMI.

During CMI usability testing, I have observed how people react to the side effects section. Most often I noticed:

people are initially quite overwhelmed by the list of side effects

once they’ve read the section—and/or answered a few questions about what to do if they experience certain symptoms—they generally seem more confident.

CMI usability testing can help you identify issues with what you’ve written in the side effects section. It can also give writers clues about how to improve or fix the issues.

If you need help writing your CMI with the new template, please get in touch. You can improve the quality of your CMI by using someone with extensive experience writing medical and health information for everyday people.

For further guidance:

Consumer Medicine Information (CMI) - How to use the improved CMI template

Sally Bathgate is a freelance health and medical writer with a decade of experience in research and the pharmaceutical industry in Australia.